How to use Story Points to Estimate a Web Application Minimum Viable Product

A user story is a concise written description that describes an item of functionality that is valuable to a user or a purchaser of a web application, preferably from the point of view of that person’s individual desires. They typically consist of three components:

- a written description of the story used for planning

- conversations about the story that serve to flesh out the details of the story

- tests that convey and document the desired outcome and can be used to determine when a story is complete

The best user stories are sufficiently small to be accurately estimable by developers and arranged in a prioritized list where a member of the development team can always confidently pick the next most important task to work on at all times during his or her work week.

But please remember that when applied properly, user stories are not just a form of requirements documentation, but are instead a placeholder for a conversation among team members. Consider that: {% blockquote Mike Cohn’s “User Stories Applied”, page 4 %} Ron Jeffries has named these three aspects with the wonderful alliteration of Card, Conversation, and Confirmation (Jeffries 2001)….Rachel Davies (2001) has said that cards “represent customer requirements rather than document them.” This is the perfect way to think about user stories: While the card may contain the text of the story, the details are worked out in the Conversation and recorded in the Confirmation. {% endblockquote %}

In short, user stories are designed to facilitate clear communication between technical and non-technical members of the project team, and to prioritize work. The collection of well-formed user stories serve as a roadmap that can help manage the uncertainty inherent in software projects.

Example User Stories

It’s best to approach them first from a very broad user-goals orientation and then refine into the minimalistic feature design that will enable those things to be accomplished.

As an inside sales agent, I want to be reminded periodically about clients I have not followed up with recently, so that I can keep my leads from going cold.

In real projects, and in order to be reasonably pragmatic, one can go ahead and lay down relatively specific design choices as soon as any can be agreed upon, so that the developers can have finer grained estimation and begin work more immediately. An example of this type of story would be more like:

As an agent, I want a weekly email notification of a list of clients I have not followed up with in the past 30 days, in order to prevent my leads from going cold.

Some other examples of user stories could be:

As a Pawn Shop Clerk, I scan a copy of the customer’s drivers’ license because the company is required by law to keep this record at least two years from the date we purchase a used valuable from a customer.

or

As an outside recruiter, I can run reports on the active positions that my firm has posted on the job board.

However, stories do not need to be so small as to describe a single data field or trivial implementation detail. To use Mike Cohn’s examples, these would be splitting the story down too far:

A user can view a job description.

or

A user can view a job’s salary range.

or

A user can view the location of a job.

Rather, this requirement can be captured with a simple:

A user can view detailed information about a job.

User Story Points

One great tool for answering the question “What should we build and by when,” is the use of User Stories to document requirements and a backlog management tool, such as Pivotal Tracker, to estimate Story Points and track developers' Velocity throughout the lifecycle of the project. The result is a continuously updated project plan that benefits from the law of large numbers to give reasonably accurate estimation by what calendar date the current phase’s functionality can be completed and for what ballpark cost.

In addition to the classic user stories that describe desired functionality from the point of view of a user, we also tend to write some infrastructure oriented stories into the backlog, like:

- Create a new Ruby on Rails project, import the Foundation CSS

- 2 pts

Some stories may describe Epics, which are features that are too big to estimate without breaking down further as it gets closer to the top of the list.

Point estimations are affixed by a round of planning poker, where the developers each pick a number and then vote on affixing a standard difficulty level. We use the 8 point scale with the following tiers:

| Point System | Hours | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| # Points | Tier Description | Low Hours | High Hours |

| 1 | Couple of Hours | 0.3 | 2 |

| 2 | Half a Day | 2 | 4 |

| 3 | Full Day | 4 | 8 |

| 5 | More than a Day | 8 | 20 |

| 8 | Too Big to Estimate, Must be Broken Down | 10 | 30 |

Please notice that as the points increase, the spread in hours from low to high for each tier increases dramatically. This captures the increased uncertainty that bigger stories represent to the project timeline and budget. Breaking larger stories into multiple smaller stories increases the accuracy of the project plan and budget projection.

Even the simplest development tasks can take much longer than most would anticipate because of the time required to perform all of the secondary tasks to test and deploy the change. This is why single point stories tend to have a higher margin of error, because it could truly be a 5 minute task or it could take 2 hours instead. While some practitioners choose to use 0 points to represent single tasks, I have found that doing so artificially reduces the team’s velocity and skews the projection of the project timeline.

Converting Story Points to a Dollar Cost Estimate

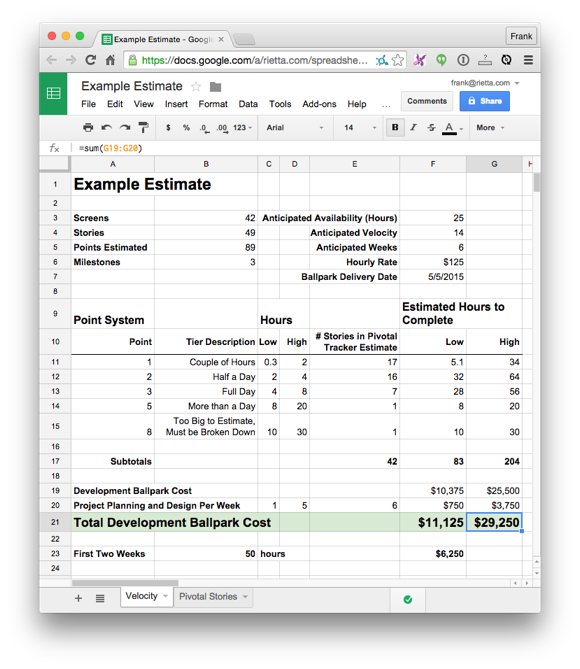

Once a sufficient number of user stories are written, at least 30 to 50 is a good start, it becomes possible to compute a ballpark budget and estimated delivery dates with a simple spreadsheet, such as shown in this example.

Further Reading

- “User Stories Applied: For Agile Software Development” by Mike Cohn (amazon.com)

- “Agile Estimating and Planning” by Mike Cohn (amazon.com)

- “Why Your Agile Team Should Use Story Point Relative Estimation” by Harry Ulrich (blog.celerity.com)